Exploring PFF Blocking Grades and Offensive Efficiency

Why the rushing offense may be impacted more in the aftermath of the Charles Jagusah injury

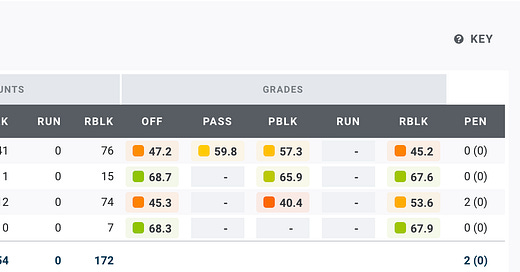

Notre Dame’s offensive line was already going to be inexperienced with Charles Jagusah in the lineup. With the left tackle lost for the season before it even starts with a torn pec, the Irish big men will be under the microscope all season long.

I wanted to investigate the relationship between PFF pass and run blocking grades and EPA/pass and EPA/rush to see where the offense may be more significantly impacted. Jagusah wasn’t a proven entity on the offensive line but with his replacement, Tosh Baker, struggling to see the field after four years in South Bend, we can project at least some dropoff in the line’s play.

The offensive line has a bigger impact on rushing efficiency

When looking at yearly team pass and run block grades and an offense’s efficiency (EPA/pass and EPA/rush), there’s a slightly stronger relationship between the rushing metrics than the passing ones.

PFF run block grade and EPA/rush R^2: 0.08

PFF pass block grade and EPA/pass R^2: 0.04

This isn’t a groundbreaking finding. A lot of previous work (at the NFL level) found that the offensive line has a larger impact on a team’s rushing efficiency than running backs.

But it’s worth discussing because it’s more evidence for a popular theory in the analytics community.

Quarterbacks control passing play outcomes, including pressures and sacks

Eric Eager, who now works for the Carolina Panthers, wrote about this topic back in 2019 for PFF, focusing on the NFL with much more granular data than I have access to.

While I can’t replicate the study Eager did for the NFL due to these data limitations, I did look at the year-to-year stability of pressure rate and pressure-to-sack rate from the quarterback and offensive line perspectives. And we do see a similar phenomenon, with quarterbacks appearing to have more control over pressure rates than the offensive line.

Pressure Rate year-to-year R^2

Quarterback: 0.23

Team: 0.16

Pressure-sack-rate year-to-year R^2

Quarterback: 0.16

Team: 0.02

In his article, Eager also found that quarterback pressure metrics were stable from the college to the pro level, more evidence that the quarterback controls their pressure rates.

While there are plays where a quarterback simply cannot prevent a pressure or sack from happening—missed blocking assignment causing a free rusher, for example—this finding makes intuitive sense.

It’s ultimately up to the quarterback to get rid of the football, whether it’s 0.5 seconds after the snap or 5 seconds. The offensive line isn’t and shouldn’t be expected to block for more than a few seconds for a play to be successful. And if an offensive line does fail early in the play, the quarterback can adjust by getting rid of the ball quicker or looking to make plays with his feet out of the pocket or by scrambling.

So, what does this mean for Notre Dame?

Well, luckily one of Riley Leonard’s best traits is his ability to avoid sacks. While he does invite a lot of pressure (34.2% for his career, 616th out of 835 qualified quarterbacks) he is elite at letting those sacks turn into pressure.

His career pressure-to-sack rate is 11.6%, a 95th percentile mark. It didn’t translate to great offensive output at Duke, only averaging 5.2 YPA when pressured for his career. But this will probably be the best supporting cast Leonard will have in his college career. Here’s to hoping his ability to avoid sacks will be capitalized on in 2024.